How helicopter boss piloted his way to a dream career

Reporter: Martyn Torr

Date published: 23 October 2012

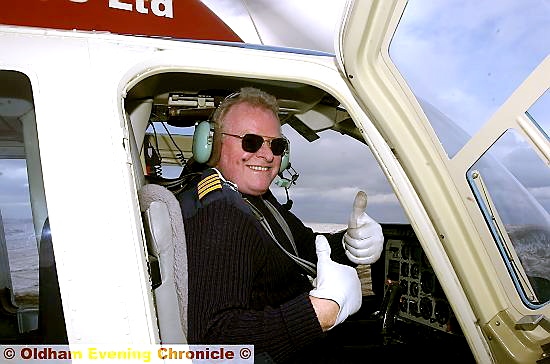

PENNINE Helicopters’ Chris Ruddy... left snow ploughs behind to set up a successful aviation business

MARTIN MEETS... Chris Ruddy, helicopter pilot extraordinaire

THERE is an inexplicable fascination about helicopters that I strongly suspect is shared by a great many of us.

But for Captain Chris Ruddy, owner and chief pilot of Pennine Helicopters, it is a fixation that has provided his living for more than 20 years - initially to support his other job, driving heavy-duty snow ploughs and gritters on the moorland roads linking Saddleworth to the West Riding.

The former school dropout — he quit Our Lady’s in Royton before sitting his O-levels — had a six-month retainer with the local authority to help clear the cross-Pennine routes.

“I remember being called up at 3am once: my job was get up to the Isle of Skye road and keep a track open by taking my digger up and down, up and down until the morning, when the snow ploughs would join me and create a passable road.

“It was a waste of time really: as soon I had cleared the track, the wind had blown it over again. It would have been far simpler to clear it just once, but that’s what we used to do in those days.”

In “those days” the winters were far worse than we endure and suffer now, he tells me with a clarity of recall that brooks no argument.

“People say we have tough winters, but they’re nothing like we had 20 and 30 years ago. Nothing at all.”

As the winters eased and the local authority retainer grew shorter by the month, Chris had to make a career change.

He sat in the dining room of his stunningly beautiful home — Oakdene Farm in the hills above Delph — and made a list of things he could do.

“I just wrote down lots of things, lots and lots. And then I stopped and took a look at the list and I had written down helicopters.”

The rest is a whirl of history...

He enrolled at flying school in Oxford — a £70,000, 12-month course requiring a remortgage of his home — and left wife Julia with new baby Charlotte to fend for themselves (with her support, naturally).

He found himself in a class of wannabe pilots from all over world, including a group from Hong Kong.

“You need a good grasp of maths for the navigation side of flying — in the main, helicopters are single pilot machines — and remember I had dropped out of school.

“But we all knuckled down except this one Hong Kong Chinese guy who had called himself Eric for the duration of the course.

“As we all struggled with the technical side of things, he would sit and read the Hong Kong Times. This infuriated our tutor who kept throwing mathematical problems at Eric, who instantly solved them all in his head. Even the spherical trigonometry calculations, though these sometimes took a few seconds longer.”

Anyway, Chris qualified as a pilot.

“It was tough, they didn’t hold your hand. In the 12 months I was down there four helicopters were written off. It was the only way to learn...”

All of this was recounted in such a matter-of-fact way as to make me wonder why I ever worried when, a few years ago, I accepted an invitation from Chris to join one his trips over the moors to the east coast.

It was an exhilarating ride but choppers are strange machines and — if you think seriously about them — they shouldn’t really work. But they do, and Chris makes them work commercially and successfully.

In addition to the pleasure flights — he now has a seven-seater — Pennine Helicopters has an increasing commercial workload, flying bales of peat and hay across the Peak National Park, helping to put out moorland fires and, quite often, flying celebrities around the region.

”I have flown them all over the years, Sir Richard Branson, politicians of all parties.

“When Sir Cliff Richard was filming ‘Heathcliff’ up here he used the farm as his changing room. What a lovely, charming polite man. He was a delight to work with.”

Courtesy was a recurring theme of our chat. Chris himself is essentially quietly spoken, relentlessly patient and impressively polite.

But there is clearly an inner core of strength which has seen him make a number of career changes and seen off challenges which lesser men may have walked away from.

Being a pilot often called out in horrendous weather conditions — he once flew for four hours to Keith near Inverness to help remove snow for the bonded warehouses of the Chivas whisky distillery — he needs to be calm and decisive and take calculated decisions.

Not risks: he never, ever takes those. But decisions.

Like when he left school without qualifications. And when he walked out of Myerscough College after three weeks - he had enrolled on an agricultural course but believed there wasn’t a future for him in farming, his first love.

He took a job with the Post office as a telecoms engineer, indulging his second love of electronic engineering.

He had acquired Oakdene Farm — a ruin — as a 19 year old and lived in a tent while he made the place habitable. “I’m still doing that now, 40 years on,” he said with a grin.

He has never been afraid of work. As a 12 year old he would hire himself out as a labourer at the many farms fringing his Royton birth place. He also rented land on which he kept hens and sold their eggs to neighbours.

“I was always hopeless at sports so when it was PE I would disappear and do some work on my land,” he recounted.

Then the headmaster — Eric Critchley — found out. “He was a man I admired hugely, a genuinely decent man and he has had a profound, lifelong effect on my life values.

“He said I shouldn’t miss lessons but if It did, and I was working on my land, then I should tell him rather than just doing it without anyone knowing.”

It was a lesson in management that has stuck with Chris to this day. Well, that and the advice Mr Critchley offered when he and a few schoolmates dropped out without qualifications.

“He said if they ask what qualifications you’ve got, tell them what they want to hear - they’ll never check and if they do, by then you will have made yourself invaluable so they will keep you on.

“To this day I have never checked the qualifications of anyone who has come to work for me. It is more important they are good people and can do the job.”

And doing the job is what Chris does best — from delivering bales of hay to being called out by the emergency services or the park authorities. But he doesn’t take every job offered.

“When the Shaw blast happened lots of press wanted me to fly over for pictures, but it wasn’t right so we said no and didn’t make the flight until the police and families were comfortable with our presence,” he said with the certainty of a man who knows and understands his role.

He’s now planning to ease his workload; the pleasure side of Pennine Helicopters is for sale. “Yes, it’s on the market, I could even sell the machine with the business and get a new heavier one to help with the commercial side, which I will continue to grow,” he explains.

Flying helicopters is part of his DNA and he expects to work for a while yet, putting out fires, delivering hay and peat.

It’s a way of life for a man who relishes a challenge and never walks away from a confrontation.

You wouldn’t expect anything else from a Royton lad who once sold eggs for pocket money and who now looks down on life from the great blue yonder.

Most Viewed News Stories

- 1‘Heartbreaking revelation’ as mass grave found in Royton Cemetery

- 2The £1m project that could transform a “scary” street in Oldham

- 3Town’s busiest road set to close for 11 nights - AGAIN

- 4The ‘high quality’ HMO that has stirred up a parking row

- 5£40m turnover Oldham-based nursery retailer has rebranded